Elites’ Long War Against the ‘Deplorables’

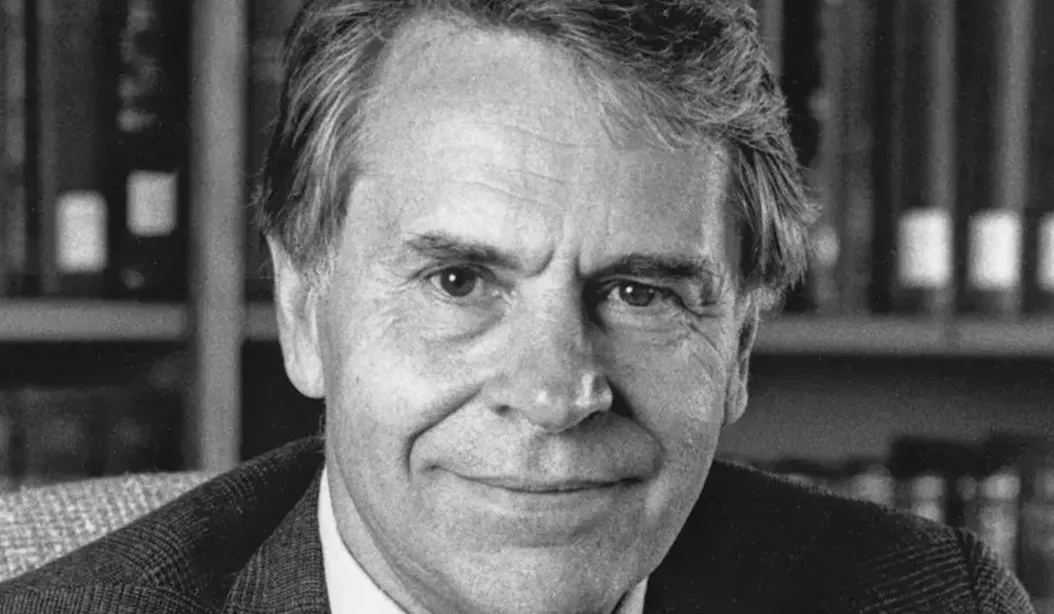

Christopher Lasch warned that America’s new elite had become detached from its roots—The Revolt of the Elites foretold our divide.

Rural Western New York has long been known as the “burned-over district,” so named for the extraordinary — even preposterous — number of religious visions that combusted there in the 1800s. It’s an apt and haunted setting for a different kind of seer who came later, this one wielding social criticism rather than scripture.

A professor of history at the University of Rochester, Christopher Lasch was one of the most engaged and erudite thinkers of the second half of the 20th century. In 1979, he appeared to reach career apotheosis when an American president, Jimmy Carter, delivered a disquisition that relied on one of his works. That book, The Culture of Narcissism (1979), was one of several deep, contrarian analyses put forward by Lasch over the years, among them Haven in a Heartless World (1977), which is his defense of the natural family, and The True and Only Heaven (1991), a rich, systematic questioning of the idea of “progress.” Though not himself a man of the right — his interest in the redistribution of wealth alone put Lasch out of fusionist bounds — he was, and remains, among the strongest allies that the socially conservative wing has ever known.

His final book, finished with the help of his daughter, history professor Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, would turn out to be the most augural of all. As happens with works that are uncannily attuned to their age, yet vaulting ahead of it, The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy (1995) didn’t bring its author worldly success. Not only did Lasch die before the book was published; on the broader stage, Americans of the mid-1990s were in no mood for such self-critical reflection. Yet the verdict of its preeminence stands. If, 30 years ago, Americans could have read just one book that would explain the seismic political shifts to come, The Revolt of the Elites would have been it...